Adrien Brody Joins Chris Evans In Apple And Skydance’s ‘Ghosted’ From Director Dexter Fletcher.

EXCLUSIVE: Following a busy fall in both the film and TV worlds, Adrien Brody is looking to stay busy as he set to join Apple Original Films’ Ghosted, starring Chris Evans and Ana de Armas. Dexter Fletcher is directing.

Skydance’s David Ellison, Dana Goldberg and Don Granger are producing, along with Jules Daly. Evans will serve as producer and de Armas as an executive producer. The film’s writers, Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick (Deadpool, Zombieland), also will be producers. They developed the project based on an original idea of theirs and pre-emptively sold it to Skydance.

The project is described as a high-concept romantic action-adventure film, and Apple acquired the high-profile project during the summer.

As for Brody, The Pianist Oscar winner’s busy fall began with his scene-stealing role in the acclaimed third season of Succession. He followed that up by reuniting with Wes Anderson on The French Dispatch. His upcoming slate including Showtime’s Los Angeles Lakers series Winning Time, where he will play iconic coach Pat Riley during the Lakers dynasty run of the ’80s. He also wrapped filming on Asteroid, another Anderson project bowing this year.

Source: deadline.com

[Photos] Adrien Brody receives the Vanguard Award onstage during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival 2021

Congratulations to Adrien Brody for the Vanguard Award onstage during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia.

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Actor/Producer, Adrien Brody walks the Red Carpet during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for SCAD)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Adrien Brody accepts the Vanguard Award onstage during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for SCAD)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Adrien Brody speaks onstage at “The French Dispatch” Q&A during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for SCAD)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Adrien Brody receives the Vanguard Award onstage during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for SCAD)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Adrien Brody attends 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival at Red Gallery on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Paras Griffin/Getty Images)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Adrien Brody attends 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival at Red Gallery on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Paras Griffin/Getty Images)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Adrien Brody poses with his Vanguard Award backstage during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for SCAD)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Vanguard Award recipient, Adrien Brody gives an interview on the Red Carpet during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Derek White/Getty Images for SCAD)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Actor/Producer, Adrien Brody walks the Red Carpet during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for SCAD)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Vanguard Award recipient, Adrien Brody walks the Red Carpet during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Derek White/Getty Images for SCAD)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Adrien Brody speaks onstage at “The French Dispatch” Q&A during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for SCAD)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Adrien Brody speaks onstage at “The French Dispatch” Q&A during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival at Trustees Theater on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Paras Griffin/Getty Images)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Adrien Brody attends 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival at Red Gallery on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Paras Griffin/Getty Images)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – OCTOBER 24: Adrien Brody accepts the Vanguard Award onstage during the 24th SCAD Savannah Film Festival on October 24, 2021 in Savannah, Georgia. (Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for SCAD)

Source: gettyimages

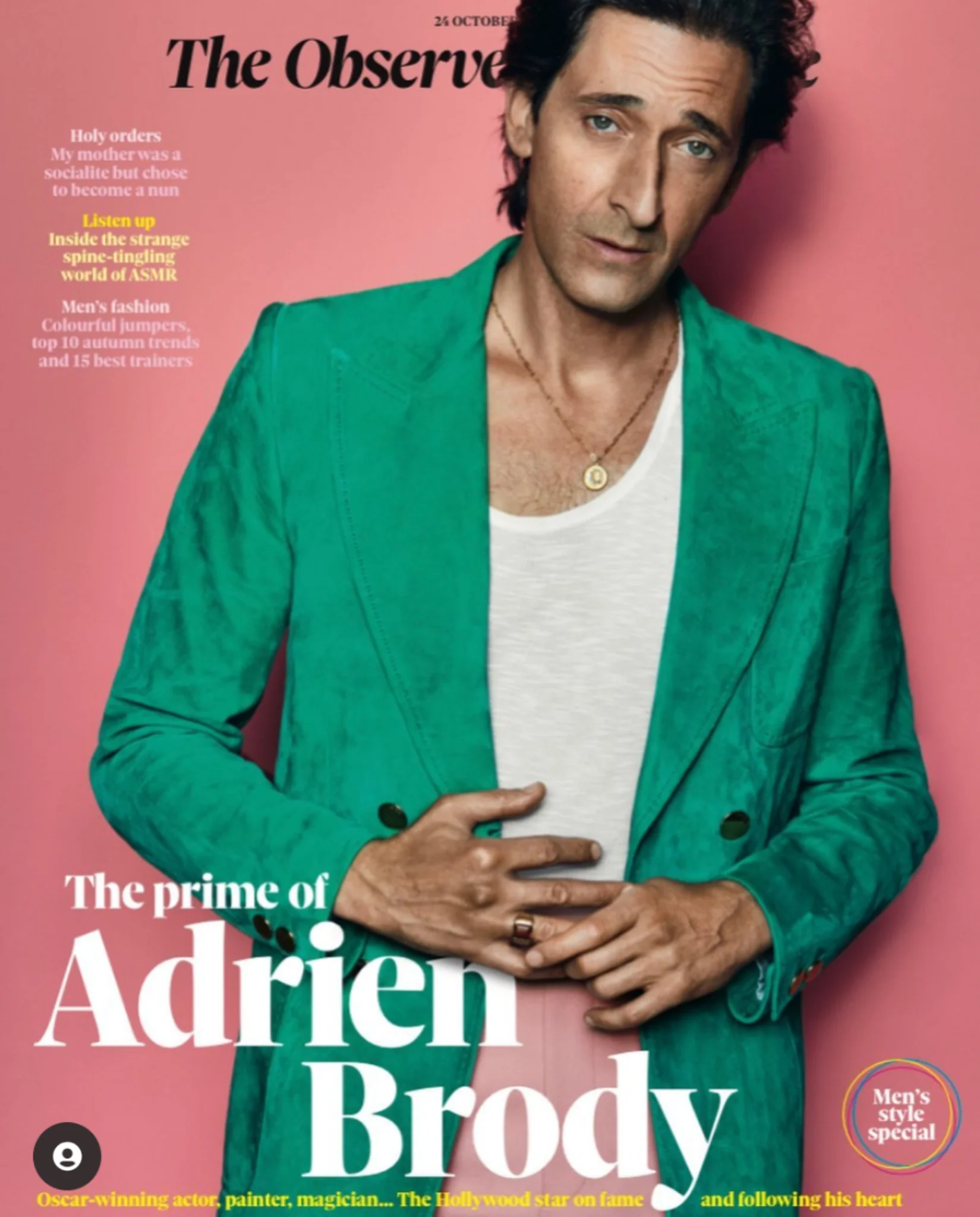

[Photos & interview: The Observer Magazine, 2021] Adrien Brody: ‘Actors are attention seekers. But I’m an introvert’

Adrien Brody could have been a magician, and now he’s rediscovering his passion for painting. But with a dizzying array of major roles and a new Wes Anderson film coming out, the Oscar-winner explains why this is very much ‘a special time’.

Roughly a year after Adrien Brody became the youngest recipient of the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role, he sat for an interview and a “glammed-up” photo shoot for the August 2004 issue of Details magazine, the now-defunct men’s publication. The cover shows Brody wearing a white T-shirt, “the perfect all-American look”, leaning backwards with both hands behind his head and meeting the camera with a gaze both remote and charged. Also on the cover, in all caps: “ADRIEN BRODY LOVES BEING FAMOUS.” Brody never said he loved being famous. It was not something he’d ever expressed. Not only was the coverline incongruous to who he was, but as an actor who’d only recently climbed into the industry’s highest level of visibility, he was still digesting the ways his life would change as a public figure. “I was so shocked by it,” he says now, over breakfast at the Whitby Hotel in New York. “It was so flippant. It just…” He hesitates, as if debating whether to complete the thought, because he is otherwise unfailingly polite. “It made me look like a dick.”

Brody is once again sitting for a cover story. He’s come straight from Good Morning America, the popular breakfast TV show, and is still wearing “make-believe clothes” lent by a stylist: a white button-up and a smart black over-shirt. His appearance this morning had gone well: “Quick and painless. It was literally two minutes. I mean, it’s a whole to-do, and then you’re on, thinking ‘I hope I don’t blow it!’ And they’re, like, ‘Good morning!’ And I’m, like, ‘Hello!’ And then they’re like, ‘Goodbye’, and then I’m like, ‘I love you, thank you!’” Because the show had run smoothly, his publicist had texted me to say he’d be early for our appointment. I arrived early, too, and through the hotel window I could see him pacing the pavement in a leisurely manner with a phone pressed to his ear, enjoying a conversation. He was talking to his father. When he breezed in minutes later – 6ft tall, a spring in his step – he smiled in an avuncular sort of way, and told his dad he had to go, that he was headed into a meeting, and that he loved him.

Brody and I are here to discuss his latest film, The French Dispatch, which follows a group of expatriate journalists and the colourful subjects of their features and profiles. I tell him it must be difficult to sit for an interview without knowing how a reporter will paint you. “I believe that you’re listening, and you don’t have your point of view to pitch, and I really appreciate that,” he says, with a shrug. After close to three decades in the film industry, he accepts that speaking to the press is part of his job. Even so, it can be frustrating to “genuinely give your time and try to share, and then it somehow becomes contorted. It’s not that it’s been edited. It becomes shifted and filtered through all kinds of different points of view. And then, depicted as you. A rendition of you.”

In The French Dispatch, Brody’s character, an art dealer named Julian Cadazio, is the one doing the shifting and filtering. After discovering a transcendent abstract painting by twice-convicted murderer Moses Rosenthaler at a high-security prison’s arts-and-crafts showcase, Cadazio vows to transform the convict into an international art star, even though he is in prison himself, for tax evasion. Cadazio demands to buy the painting and asks the artist to share his life story: “Where did you learn? Who did you murder?” He wants the gory details so he can commission a biography, generate hype and boost his own profile. There’s only one problem: Rosenthaler doesn’t care about any of that. He just wants to continue painting his muse, Simone – who also happens to be the warden.

The French Dispatch, which is directed by Wes Anderson, is structured like a magazine issue, with six sections united by the fictional magazine’s journalists, who narrate each of the short films. Brody’s storyline, titled The Concrete Masterpiece, functions as a parable about the commodification of art and artists. “Adrien’s character says – and I’m paraphrasing – that the whole point of an artist making art is to show it,” Benicio del Toro , who plays Rosenthaler, told me. Brody and del Toro discussed that matter at length. “It’s the same for film people,” del Toro continued. “Being an actor in movies is very similar. There’s no movie without an audience. There’s no artwork without an audience.”

Brody was born in 1973 in Woodhaven, Queens, to the longtime Village Voice photographer Sylvia Plachy, whose photographs were acquired by the Museum of Modern Art when she was in her 20s, and Elliot Brody, a professor and self-taught painter. Even as a boy, the young Brody loved to act. “I would often reenact things I saw that were interesting to me…” he says, “specific mannerisms, or retellings of conversations and experiences that struck me as unique.” For a while, he performed magic tricks at friends’ birthday parties, using the moniker the Amazing Adrien. When his mother learned about the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, through a photography project, she encouraged him to enrol in acting classes. At 12, he started performing in theatre productions around New York; a year later, he played the lead character in Home at Last, a historical film for public television about a city-dwelling orphan who gets adopted by a family in Nebraska.

As a child, Brody was also a prolific painter. He applied to study fine art at Fiorello H LaGuardia High School, which is best known as the performing arts high school in Fame. He was rejected. But in a fortuitous plot twist, he was accepted by the drama department. So while some of his friends became active in the street art movement of the 1990s, Brody was busy acting in films like Francis Ford Coppola’s New York Stories and Steven Soderbergh’s King of the Hill. He received rave reviews for his breakout role in Spike Lee’s Summer of Sam, in which he played a punk outcast. And then he landed the lead in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist, which would earn him the Oscar.

Throughout the 2000s, Brody became one of the most in-demand actors on the planet. He appeared in M Night Shyamalan’s The Village, Peter Jackson’s blockbuster King Kong remake, and The Darjeeling Limited, his first Wes Anderson film. “I tried to respond to material without the same point of view I had before,” he remembers, “which was to take risks, to explore interesting, different characters and genres.”

But roughly a decade ago, he became frustrated by the fact that no matter how much work he put into a film, it would never fully match his vision for it. As an actor, he realised, he could only ever be one part of a director’s idea – a cog in the machine – and that his performance would be “enhanced or diminished by the collective work of the people around you”. Brody became downhearted by Hollywood, which necessitated him accepting parts in big-budget films he found less valuable. “If you do really interesting independent movies that don’t open, then you don’t have a lot of value, in the business sense,” he says. “With regards to your cachet and your ability to find yourself in meaningful roles in bigger movies that require a bigger investment, those are exclusive to those who are bringing in bigger numbers. And the only way to bring in bigger numbers is, you have to do a certain type of film.”

Eight years ago, the French artist Georges Moquay visited Brody’s house in upstate New York to work on some paintings. The pair had hit it off at Art Basel, where Moquay had shown his work years earlier. There was some leftover canvas laying around, so Moquay suggested Brody pick up a paintbrush and make something with it.

“I did,” Brody remembers, “and he freaked out on it. He was like, ‘Why aren’t you painting?’ I said, ‘I don’t know!’”

Brody realised painting could fully belong to him in a way acting couldn’t; it could be his medium for constructing tiny, private worlds. “I felt such creative freedom,” he says – in some ways, more creative freedom than he’d felt in Hollywood. Since then, he has rented studio space wherever his films are in production, and is now in the process of building “a massive studio in the countryside”. Lately, he’s been doing a lot of collages, partially inspired by the layers of paper and paint he would notice on the walls of New York as a kid. “There’d be something scratched off and written, partially legible, and some old advertisement that was torn away, and I would just love that.”

During the pandemic, Brody’s art practice served him well. While shooting See How They Run, a midcentury, London-set whodunit co-starring Sam Rockwell, Saorise Ronan and David Oyelowo, Brody stayed home and painted when he wasn’t on set during lockdown. “I’ll be broken from painting on the floor for a week straight, like, it’s hard to get out of bed. It’s crazy how immersive it is, at times.” He shows me a few studio photos on his phone, and I realise he’s not exaggerating; Brody paints 16ft canvases on the floor, like Jackson Pollock minus the splatters. It really does look like a workout.

“They say actors really are attention-seekers, but I’m very introverted,” he explains.

In 2016, Brody stopped looking for work altogether. “I had some previous work that was still coming out, but I passed on most acting projects for several years,” he says. But recently something has shifted. We talk about the dizzying six projects he has shot over the past two years: The French Dispatch, Succession, the Stephen King adaptation Chapelwaite, the Netflix Marilyn Monroe biopic Blonde (in which he plays an Arthur Miller-like character), See How They Run, and the as-yet-untitled Adam McKay HBO series about 1980s era LA Lakers, where Brody stars as legendary coach Pat Riley.

“I feel like there’s more, actually,” he says, sprinkling hot sauce on some scrambled eggs. There’s Clean, the Tribeca film he scored, starred in, and co-wrote, plus a script he’s currently writing, which began as a feverish brainstorm in the halls of the Prado Museum, in Madrid. He seems to have more creative energy now than ever. “It’s a special time,” he says, with a twinkle in his eye. “I can’t really put my finger on what it is. Maybe it’s something within me, I’ve welcomed more in.” He expresses gratitude that “interesting filmmakers” are approaching him with “well-written characters.”

The French Dispatch marks Brody’s fourth collaboration with Anderson. (He recently signed up for a fifth, Asteroid City, which will be set in Spain.) Anderson sets are “unique environments” that extend beyond the film itself, Brody says. “Everyone comes home to the same hotel and we all have dinner together every night.” He makes the production sound like a roving summer festival, or a close-knit theatre troupe. (Del Toro, “the new kid,” says Brody was “very welcoming and generous, and he quickly made me feel like I was a part of the troupe. I’m very grateful for that.”)

“So often, when you’re away and you’re on location, everybody has their own lives, they’re all busily dealing with their own thing. It’s far less of a community than it could be,” Brody says. “Wes creates this sense of everyone joining the conversation.” He became hooked on the approach after their first movie together, The Darjeeling Limited, which co-starred Owen Wilson and Jason Schwartzman and was shot almost entirely on a hired train in India. “It was like a group of brothers – we were experiencing all these things as we were doing them.”

There is precise choreography to an Anderson scene, he explains, because a “rigorous” level of detail is required to hit each beat. “He hears the music,” Brody says of Anderson. As an actor, “you have to be able to hear that music and catch it.” Especially during a scene like the grand finale of his French Dispatch storyline, a long tracking shot where the cast fires off lines like dominoes, “you really don’t want to be the weak link” who flubs the line, he says, forcing the entire scene to reset. “You have such a responsibility to lift everyone else up.”

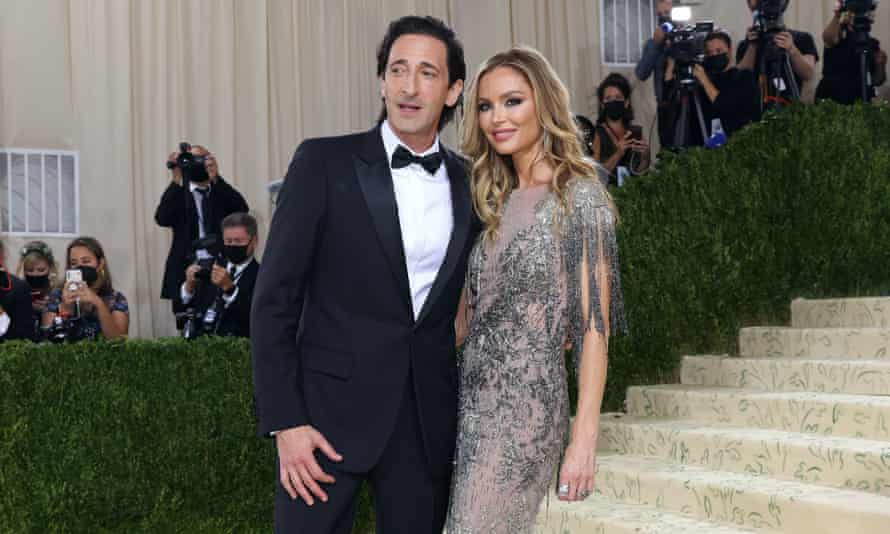

We pay the bill and leave the restaurant. He’s meeting his girlfriend of two years, Georgina Chapman, the Marchesa designer and ex-wife of Harvey Weinstein. (The pair confirmed their relationship earlier this year on the red carpet of the Tribeca Film Festival, and have since made appearances at Cannes and the Met Gala.) After lunch, he plans to visit his parents in Queens before boarding a flight to Los Angeles to resume shooting Adam McKay’s HBO show.

There are two cars waiting for him outside the hotel: a black Mercedes with a driver and a compact black sedan driven by Chapman. He’s getting into the car with Chapman, so he offers to let his driver take me to my next appointment downtown.

Though he’s been a fixture in American cinema for years, Brody still seems like a puzzle to many fans, which isn’t a bad thing in an era defined by its online self-mythologising. “I feel like it’s difficult for people to separate who you are from who they think you are, and the characters that you played. Now they just Google who you are, and get whatever someone else has thought or said about you,” he’d told me earlier. “If you look at my work, it’s very hard to say, ‘This is the kind of actor that he is.’ ‘This is the kind of person that I am.’”

And you feel that’s the way he likes it.

The French Dispatch is out now

Stylist Christian Stroble; stylist’s assistant Makaela Mendez; digital Maria Noble; lighting Kendall Connorpack, Sebastian Keefe and Tobey Lee; grooming Natalia Burschi using for hair R+Co, and Makeup, Tom Ford.

[Fotos & entrevista: GQ magazine, 2021] Adrien Brody ha encontrado su lugar.

Casi 20 años después de ganar un Oscar y reclamar su título como uno de los actores más serios de su generación, Adrien Brody ha hallado una nueva motivación.

Adrien Brody llega pertrechado con fruta. Nos citamos en el parking de una popular ruta de senderismo de Los Ángeles, y rápidamente me entrega los snacks que ha preparado: un recipiente de plástico lleno de cerezas y sandía, junto con un par de botellas de agua, zumo de naranja recién exprimido y dos panes tostados con mantequilla envueltos en una servilleta. Es un tipo encantador, sin duda, pero también un actor al que le gusta hacer un profundo trabajo de preparación, sin importar el papel. Comemos sentados en un banco. Aún no son las nueve de la mañana. Las cerezas están riquísimas.

Brody tiene 48 años y lleva 30 actuando profesionalmente. En este tiempo, se ha hecho conocido por la intensidad con la que afronta su compromiso con el trabajo: perder peso, ganar músculo, gatear por el bosque… “Hago lo que sea necesario por un papel”, dice, “y todos en mi vida lo entienden y lo respetan”. Como todos los actores, ha tenido altibajos, pero tal vez debido a esa intensidad, los altos de Brody han sido más altos, y sus bajos, tal vez más bajos, en comparación con muchos de los intérpretes que consideramos sus compañeros y a quienes llama amigos. Sigue siendo el hombre más joven en ganar el Oscar a mejor actor en la historia de los premios de la Academia. Y también decidió, no hace mucho, pasar unos años haciendo cualquier cosa menos actuar.

Este otoño será un periodo inusualmente prolífico para el actor. Está en la tercera temporada de Succession, en la que interpreta a un inversor activista que se enfrenta a la familia Roy. Después viene The French Dispatch, su cuarta película con el director Wes Anderson (la quinta ya está en camino). Y en algún momento del próximo año lo veremos dando vida a dos figuras legendarias: el dramaturgo Arthur Miller, en Blonde –la película de Netflix sobre la esposa de Miller, Marilyn Monroe–; y el entrenador de baloncesto Pat Riley, en la serie de HBO de Adam McKay sobre la era del “Showtime” de Los Angeles Lakers en la década de los 80. Muy consciente del componente azaroso que rige la carrera de un actor, está emocionado de que haya tantas cosas sucediendo a la vez. “He hecho muchas cosas divertidas, pero ahora estamos en un buen momento”, dice.

Brody siempre ha aplicado su método del máximo esfuerzo a todo, sin importar la calidad del material. De hecho, no han sido pocas las veces que su trabajo ha sido lo único salvable de ciertas películas. Ahora, sin embargo, tiene una serie de papeles en proyectos del más alto nivel que finalmente parecen estar debidamente calibrados a sus habilidades, y eso podría mostrarle al público un Adrien Brody diferente.

La serie de los Lakers todavía está en producción el día que nos encontramos. Mientras comenzamos nuestra caminata, Brody –con botas de montaña, una gorra de los Yankees y gafas de aviador oscuras– explica que algo un poco extraño está sucediendo con el papel de Riley.3 Brody no sabía mucho sobre el entrenador antes de prepararse para el personaje, pero rápidamente se enteró de que la historia de Riley era más compleja de lo que pensaba. Antes de que Riley se convirtiera en un entrenador reconocido en el Salón de la Fama, había sido una estrella de baloncesto universitaria y luego jugador suplente en un equipo de los Lakers que ganó el título. Después de una carrera profesional de nueve años, Riley se retiró a los 30 y, como dice Brody, “se encontró en Los Ángeles tratando de averiguar cuál era su lugar dentro del mundo del deporte y sin ser capaz de aceptar la jubilación anticipada”. Riley terminó a cargo del que se convertiría en el equipo insignia de la década de los 80, pero sólo después de que el entonces entrenador de los Lakers sufriera un terrible accidente de bicicleta y de que el entrenador asistente que lo reemplazó fuera despedido. “La desgracia de un hombre creó una oportunidad para otro”, explica Brody. McKay, el director, y Max Borenstein, el escritor de la serie, necesitaban un actor que pudiera reflejar la dualidad de espíritu del entrenador. Brody parecía perfecto, “porque es una mezcla única de elegante confianza y vulnerabilidad”, me dice McKay en un correo electrónico. “Y ésa es una descripción perfecta de Riley. Aunque, obviamente, Riley no muestra la vulnerabilidad ni se siente tan cómodo con ella como Adrien. Pero puedes ver claramente que está ahí”.

Ése es el Riley en el que ha estado pensando: no el icono fanfarrón y con traje Armani, sino un joven preocupado porque sus mejores años han quedado atrás, desconcertado por las circunstancias que le han llevado a ocupar su posición en la vida.

Es gracioso, dice Brody, lo mucho que la historia de Riley se parece a la suya. Vivir con ese espejo delante durante estos últimos meses le ha hecho pensar en la extraña tormenta que se desató sobre su vida y su carrera después de ganar el Oscar, en 2003, por su trabajo en El pianista. En aquel entonces, Brody tuvo que luchar con el mismo tipo de contradicción que enfrentó Riley cuando le entregaron las riendas de los Lakers: estaba aparentemente en la cima del mundo y, sin embargo, se sentía incapaz de controlar la trayectoria de una carrera que había alcanzado el punto más alto demasiado temprano. En el caso de Brody, la avalancha de fama y trabajo que siguió a la película le proporcionó una cierta seguridad, pero la experiencia también lo dejó deprimido y con un trastorno alimentario, y reordenó permanentemente las expectativas, tanto de la industria como suyas, sobre la dirección de su carrera y el significado del éxito.

Mientras explica todo esto, deteniéndose en divagaciones sinuosas sobre la naturaleza de la suerte y los caprichos de la producción cinematográfica independiente, un excursionista con la piel bronceada y un marcado acento neoyorquino nos detiene en medio del camino. Reconoce al actor y se presenta como Jack. Nos cuenta que conocía a Gerald Gordon, un profesor de interpretación con el que Brody dio algunas clases cuando se mudó por primera vez a Los Ángeles. Jack explica que Gordon le había dejado instrucciones de enviar sus mejores deseos a Adrien Brody en caso de que un día se lo encontrara. Lo que sonaría al delirio de un loco si no fuera porque es exactamente lo que acaba de suceder. Jack parece tan confundido como nosotros. Brody ofrece su agradecimiento y termina elegantemente la conversación.

Quizás gracias al entrenamiento de Brody como actor, o quizás sólo a su sensibilidad congénita, eventos monótonos como éstos –una caminata, una charla con un amigo de un viejo maestro, una discusión sobre en qué está trabajando estos días– parecen imbuidos de una gravedad especial cuando él los toca. A lo largo de nuestro tiempo juntos, aprendí que las metáforas tienden a seguirlo, algunos días como una camada de cachorros, otros como una colonia de avispas enojadas.

Durante toda su carrera ha puesto cada gramo de sí mismo en los papeles que ha interpretado. Pero ahora mismo, con el trabajo de Riley y todo lo que le rodea, parece listo para aprender de nuevo. Abundan las lecciones útiles, si uno está dispuesto a escuchar. “Solo estoy tratando de vivir abiertamente y sin miedo”, me dirá más tarde.

Al subir una colina, Brody acelera el paso. Se voltea hacia mí. Llevamos caminando unos 15 minutos. “Así que, de todos modos”, dice, “así es cómo, si tienes suerte, acabas abriendo nuevos capítulos en tu vida”.

Brody se tiró todo el verano grabando la serie de los Lakers en varios lugares de Los Ángeles. Todas las mañanas doblaba su cuerpo larguirucho para meterse en su Fiat con cristales tintados, trucado, con palanca de cambios, y lo conducía desde su casa en The Hills hasta el lugar donde se rodara ese día. Rápidamente llegó a amar el trayecto, o tal vez menos el trayecto específico que la pequeña alegría de tener finalmente uno que hacer. Gran parte de su trabajo como actor se ha desarrollado en localizaciones menos cómodas. Hace mucho tiempo se dio cuenta de que su amigo Owen Wilson, de alguna manera, se las arreglaba siempre para terminar actuando en películas que se rodaban en su misma ciudad. Brody no tenía tanta suerte. “Si Owen vivía en Santa Mónica, hacía una película en Santa Mónica”, dice. “Yo ya podía estar rodando en Bulgaria en invierno que a Owen le tocaría bajar a Santa Mónica, a cinco manzanas de su casa, y probablemente hasta podría irse a casa a comer. Es algo asombroso”, asegura, tener un trabajo al que puedes ir en coche.

Es cierto que, si tuvieras que hacer una película ambientada en Santa Mónica, probablemente no elegirías a Adrien Brody. Sin embargo, si tuvieras que hacer una película que necesitara un rostro de Europa del este distorsionado por el sufrimiento, o si requirieras el tipo de actor que podría considerar una producción independiente de bajo presupuesto en los Balcanes como una especie de aventura gloriosa, Brody sería tu mejor opción.

Parte de esto es anatomía simple. Tiene la nariz recta y respingona, los ojos verdes amplios y hundidos, y un par de cejas arqueadas en permanente expectación. Parece irónico pero también un poco triste. Su voz, ronca, nasal, salpicada de sabiduría, parece atemporal. Wes Anderson aprecia esta cualidad. “Una cosa rara de Adrien es que, si tuviera que trabajar repentinamente alrededor de 1935, en lugar de en 2021, podría hacerlo”, me dice en una nota de voz narrada de manera divertida, compuesta en respuesta a mis preguntas.

Brody lo acepta todo honestamente. Su madre, la fotógrafa Sylvia Plachy, se fue de Budapest a Viena cuando era adolescente, en la época de la Revolución Húngara, y finalmente llegó con su familia a Nueva York, donde más tarde comenzaría a filmar para Village Voice. La vida y el trabajo de su madre le di ron la capacidad de “ver la complejidad que la mayoría de las personas se pier- den, en todas partes, a su alrededor, y poder captarla; e inmortalizarla. He visto el mundo a través de esa lente”, dice. Era un niño sensible al que le molestaba serlo, hasta que se dio cuenta de que esa cualidad también podía ser un regalo. Actuar le abrió una nueva forma de relacionarse con el mundo, dice: “Afortunadamente, había estas escapatorias: seres humanos maravillosamente complejos en los que me podía convertir, con los que podía relacionarme de una forma u otra. Y purgarme, supongo, o participar en el sufrimiento de otro ser humano, y no sentirme solo en el mío. Y luego comprender la universalidad de todo nuestro sufrimiento y alegría, pero abrazar los momentos de alegría y honrar el vasto sufrimiento que, lamentablemente, es la capa subyacente generalizada”.

Mamá regresó de un encargo para filmar en la Academia Estadounidense de Artes Dramáticas con la sensación de que a su hijo único, mago amateur y artista natural, le gustaría estudiar interpretación formalmente. En poco tiempo, estaba asistiendo a cuatro clases al día en LaGuardia High School y preparando un papel para Francis Ford Coppola en New York Stories.

Ese trabajo de un día le brindó lecciones que perduraron. El guion decía que un par de chicas tenían que mostrar una fuerte aversión a la horrible colonia que usaba el personaje del adolescente Brody, así que el director lo roció de arriba a abajo. “Coppola decidió usar la técnica del Método y me echó una botella de colonia asquerosa encima, para que las chicas tuvieran algo a lo que reaccionar”, recuerda Brody.

A los 19 años, Steven Soderbergh lo dirigió en su película sobre la era de la Gran Depresión, El rey de la colina. Anderson recuerda que la vio con Owen Wilson y que la actuación de Brody lo cautivó al instante. “Era una de esos trances en los que puedes sentir de inmediato que estás delante de una estrella de cine”, asegura. “De algún modo, él se sobrepone a todo con una sonrisa, y parece tan relajado… Simplemente te atrapa, instantáneamente “.

Por un tiempo, el estrellato pareció serle esquivo. Obtuvo un papel importante en La delgada línea roja, pero sólo para enterarse después de que el director Terrence Malick lo había excluido de casi toda la película; y realizó algunas escenas en Summer of Sam de Spike Lee como un punk libertino de Nueva York. Brody siguió intentándolo.

Mientras hablamos, el sendero se termina y acabamos fuera del cañón, en una calle tranquila –un frondoso callejón sin salida rodeado de grandes casas–. Más adelante está el camino que nos conducirá suavemente colina abajo, hasta el lugar donde dejamos nuestros coches. Pero Brody tiene una idea diferente. “Conozco otra salida”, dice, y añade una pequeña advertencia. “Pero es una locura”. Efectivamente, localiza un nuevo rastro. Es un camino estrecho y empinado de una sola pista que en ese momento hierve al calor del mediodía. Lo tomamos.

Es el don de Adrien Brody, pero quizás más a menudo su maldición: que vive para los papeles difíciles. Y no sólo los difíciles, sino también los que lo golpean físicamente, los que ponen a prueba su cordura. “Siempre me digo: ‘¿Por qué elegí esto? ¿Por qué quiero hacer esto? Estoy muy dispuesto a hacer casi cualquier cosa por un personaje. He comido gusanos. He comido hormigas. He saltado de helicópteros. Y solo después dices: ‘Guau, eso fue realmente estúpido. ¿Por qué hice eso?”.

La respuesta es siempre la misma: “Porque no quieres tener miedo. Esa sensación te nubla el juicio y acabas aceptando”.

Tenía 27 años cuando Roman Polanski le dio la oportunidad de poner a prueba sus principios sobre la actuación y el sufrimiento. En El pianista, una historia real de resistencia y devastación, interpretó al personaje principal, Wadysaw Szpilman, un músico judío que sobrevivió a la ocupación nazi de Varsovia. Para prepararse, Brody transformó su vida. Vendió su coche y desconectó sus teléfonos. Abandonó su apartamento y guardó sus cosas en un trastero. Pasó días enteros en habitaciones de hotel en Alemania y Polonia, practicando el piano.

“Fue una enorme responsabilidad y me cambió”, dice. Físicamente, el rodaje fue una pesadilla. Al terminar la producción, estuvo deprimido un año. Le desagradaba su cuerpo, devastado por una dieta de choque que bajó su peso hasta los 60 kilos. Todo el asunto le dejó con una tristeza que aún perdura. “Pero no tenía idea de lo que vendría”, dice. “No tenía ni idea.”

“Aspiré por más, y me pareció que mi teoría de contribuir y verter mi sangre, sudor y lágrimas en un proyecto no dio los resultados”.

Por supuesto, El pianista fue recibida con entusiasmo, en especial por la inquietante interpretación de Brody. Fue nominado para un premio de la Academia y, en apariencia, fue admitido en ese reino reservado para los mejores actores, o los más comprometidos, o los más locos. Se instaló en la imaginación del público como quizás el próximo Robert De Niro o el próximo Daniel Day-Lewis, el protagonista desquiciado, no canónicamente guapo pero obviamente sexy, que será la primera opción de cualquier director para todas las películas dramáticas por el resto de su vida.

La semana de los Oscar, Brody recibió una llamada de Jack Nicholson; ambos estaban nominados a mejor actor, junto a Day-Lewis, Michael Caine y Nicolas Cage. Estados Unidos acababa de enviar tropas a Irak, y Jack convocó a los nominados en su casa para coordinar una respuesta. Fue un shock. La primera vez que hablaron, asegura Brody, le llamó Brophy. “Y ahora Jack va y me invita a su casa. Y estoy ahí con Michael Caine y con Nicolas Cage, y ellos están bebiendo whisky y fumando puros y estamos sentados en un pequeño círculo”. Todos menos Brody ya habían ganado un Oscar. Nicholson sugirió que no asistieran al espectáculo, en protesta por la guerra. Brody dijo: “Oíd, no sé vosotros, chicos, pero yo sí voy a ir. Aunque estoy de acuerdo con vosotros: creo que quien suba al escenario tiene la responsabilidad de hablar de lo que está sucediendo”. Simplemente no pensó que fuera a ser él.

Pero fue él. Brody no esperaba ganar: la mañana del espectáculo, recuerda estar sentado en la acera de Beverly Boulevard frente a un restaurante en Hollywood, abrumado por la enormidad de todo, mientras sus padres, que estaban de visita, esperaban a que se recuperara. Pero la victoria tampoco fue una tontería. Había puesto todo lo que tenía en el papel, y la experiencia pareció solidificar su convicción de que, con suficiente esfuerzo, podría encarnar y retratar los extremos más crudos de la experiencia humana. Era una locura pensar que podía estar cerca de comprender el sufrimiento de un superviviente del Holocausto como Szpilman, pero había una especie de euforia en el esfuerzo de intentarlo. “Fue la cosa más dura que he experimentado en mi vida. Después, cada vez que me he revolcado en mi propio sufrimiento, he tenido esa perspectiva”, dice. Aprendió una lección simple e indeleble: el arte con mayúsculas es doloroso. Por eso es también prácticamente el único tipo de arte que vale la pena intentar.

Su secreto, si se puede llamar así, era que no siempre actuaba. “He trabajado con actores que son brillantes y no parecen falsos, pero apenas saben actuar. Saben crear”, dice. “Es un truco de magia maravilloso. Saben actuar como si te quisieran, y realmente no es así. Y a mí me cuesta trabajo”. En una escena de El pianista, tenía que trepar por una pared, lesionarse el tobillo mientras aterrizaba del otro lado e irse cojeando. Así que se metió una piedra afilada en el zapato. Dolía al aterrizar y luego al caminar también. “¿Para qué molestarse en fingir una cojera?”, pregunta ahora. “Sólo duele durante un minuto. Simplemente hazlo”.

Incluso ahora, que se está metiendo en la piel de una serie de iconos viriles de la masculinidad estadounidense, como Riley en Succession –al que Brody llama su “tiburón”– o el esposo de Marilyn Monroe, esta forma de pensar es útil. “No hay arrogancia sin sufrimiento”, dice. “De hecho, la chulería de la mayoría de la gente suele ser el resultado de mucho sufrimiento”. La arrogancia, razona, puede ser en sí misma una especie de cojera.

Es posible que el público sólo capte los más pequeños destellos de esto: la armadura de dolor que Brody construye debajo de la superficie de cada personaje. Pero sabe que está ahí. “Eso es esencial, al menos para mi proceso”, dice. “No siempre necesito una piedra. Pero a menudo tengo una piedra”. Una piedra real, aclara, puede ser útil para transmitir todo tipo de emociones, incluso si su personaje no tiene problemas en los pies.

“Ahora estás conociendo todos mis secretos”, dice riendo. “Mierda. Incluso cuando no estoy cojeando. Por eso parezco tan melancólico. Tengo una maldita piedra en el pie”.

Una cosa que Brody enfatiza mientras caminamos es cuán improbable era que sucediera todo esto: cuántas cosas pequeñas e imposibles tienen que salir bien para hacer cualquier película, y mucho más una que impulsa a su actor a través de la temporada de premios para acabar convirtiéndolo en un icono hollywoodiense. “Sabes, esas cosas no suceden prácticamente nunca”, dice. “Pero puedes tener la expectativa de que deberían suceder con regularidad”.

Le llevó un tiempo superar esa expectativa, por lo que los años que siguieron a su victoria en los Oscar le des- orientaron. “Llevaba 17 años actuando, así que la gente me reconocía y era normal”, dice. “A los paparazzi no podía importarles menos. Nadie me seguía. Nadie se comportaba de forma extraña. Nadie hacía cosas raras. Y luego, de repente, todo empezó a ser muy extraño”. Después de ganar el Oscar, no volvió a tener una interacción igual con ninguna persona. “Fue como si hubiera entrado una tormenta”, dice. “Todo comenzó a volar, la vida que conocía”.

No cambies, le decía la gente. No cambies. Y él no lo hizo. Pero todos los demás sí. Le hablaban de una manera diferente. Los amigos querían hacer negocios con él. Los fotógrafos querían tomarle fotos. Los directores lo querían para sus películas. Nada de eso le sentó muy bien. “Es como si me hubiera llevado una década descubrir quién era y dónde estaba. Mucho vivir y perder, y ganar y perder”, dice.

Durante un tiempo, tuvo la inusual mala suerte de aparecer en varios proyectos fallidos de cineastas de éxito. Hizo The Village, el primer gran tropiezo de M. Night Shyamalan. El remake de gran presupuesto de King Kong, de Peter Jackson. La lúgubre película de Wes Anderson Viaje a Darjeeling. The Brothers Bloom, de Rian Johnson. To-as eran elecciones lógicas, por sus propios méritos; todas las actuaciones caracterizadas excepcionalmente con el intenso elemento melancólico de Brody; todos los resultados desafortunados, según la dura crítica de Hollywood.

Soñaba con escaparse, con encontrar un lugar en el norte del estado de Nueva York, el tipo de casa que su padre habría marcado en los listados de inmuebles cuando era niño. Sus amigos Mark Ruffalo y Vera Farmiga vivían en refugios alejados de la ciudad, lo que demostraba que escapar no era incompatible con una carrera en Hollywood. Estaba saliendo con la actriz Elsa Pataky en ese momento, y pensó que podrían hacerlo juntos. “Recibí demasiada atención para mi gusto, y pensé que podría buscarme un lugar apartado, entrar, hacer mi trabajo y retirarme otra vez… No sé por qué, pero imaginé que sería fácil”.

Pero tratándose de Brody, no fue fácil. Estaba trabajando en una película en Serbia cuando encontró Stone Barn Castle en un listado de inmuebles. La enorme casa de guijarros unidos por cemento, a unas cuatro horas de la ciudad de Nueva York, tenía establos para caballos e incluso un huerto de manzanos. Brody se enamoró de ella. “Soñaba con algo dramático”, dice. La compró y sorprendió a Elsa con ella.

Se pusieron a hacer una renovación masiva. Pero la relación terminó antes de que pudieran mudarse de la casa de huéspedes al edificio principal.

Pasarían todavía tres o cuatro años antes de que Brody lo estrenara, tan intensa era la reforma. Lo que comenzó como un lugar para escapar se convirtió en un proyecto que lo consumía todo. Viajó a India y China para encontrar los materiales adecuados. Compró ventanas de iglesias y vigas talladas a mano en granjas de Nueva York, Pensilvania y Canadá. Tuvo un equipo sólo para repasar las piedras durante cuatro años. Consejo gratuito de Adrien Brody para remodelar el hogar: no te preocupes por repasar las piedras. “Contraté a un grupo de hombres para que esculpieran cada piedra, bajo tierra y en la parte de arriba. Y luego, cuando todo estaba terminado, se veía igual. Un poco más ordenado”. Ese sentimiento impregnaba todo el proyecto: “Todavía no sé cuál es realmente su propósito”, dice. “Pero es un logro”.

Y luego, hace cinco o seis, o tal vez ocho años, se dio cuenta de que su trabajo diario no se estaba volviendo más fácil. Seguía aplicando el esfuerzo maníaco que lo llevó a la fama, pero el trabajo ya no parecía compensar el esfuerzo. “Hubo un largo periodo de tiempo en el que me di cuenta de que ese camino no estaba funcionando, por alguna razón”, dice. “Aspiraba a más, y sentí que mi teoría de contribuir y verter mi sangre, sudor y lágrimas en un proyecto no estaba dando los resultados que esperaba. Hubo una desconexión, de alguna manera, con lo que había hecho durante tanto tiempo, y simplemente no estaba funcionando”. Así que dio un paso atrás. Terminó los proyectos en los que estaba trabajando y rechazó los que venían. Se dejó crecer el pelo y la barba. Salió con artistas y comenzó a pintar. Hizo música. Viajó por el mundo.

Con el tiempo, estos pasatiempos dejaron de ser meras distracciones del mundo de la actuación y se convirtieron en formas de reforzar su fe en su propia creatividad: formas diferentes, y a menudo menos dolorosas, de canalizar su energía. “Eso es vivir, no huir”, dice. “Es estar presente con algo y tratar de crear algo que perdure”.

Inicialmente, nuestro plan era reunirnos nuevamente el día siguiente para conversar durante la comida. Pero mientras comemos en el estacionamiento después de nuestra caminata, pensamos: ¿por qué no volver a hacer esto mañana? Tendremos que levantarnos un poco antes, para tener en cuenta el calor, pero Brody está de acuerdo y yo también. Más tarde, esa noche, me envía las coordenadas que debo seguir, a las 7:30 de la mañana siguiente, para llegar al principio de un sendero cerca de un espeluznante zoológico abandonado. Esta vez, Brody ha empacado un recipiente de melocotones y naranjas en rodajas, y trae pequeños tenedores de ostras que usamos para comer la fruta.

Casi de inmediato, Brody centra su atención en una ardilla escondida en una roca cercana. Se agacha, deseando que la criatura se acerque, y se disculpa con ella por no haber traído comida. “Lo siento”, dice. “No he venido preparado porque no sabía que iba a conocer a un tipo tan tierno”. Brody es paciente y está quieto, y funciona: la ardilla se acerca unos centímetros, luego se retira y luego se acerca de nuevo. Repiten el baile hasta que el animal está a un centímetro de la mano de Brody. “Adrien Brody imita con realismo el ruido de la ardilla”, dice, anticipando cómo aparecerá la interacción en esta historia, “y luego se comunica con el animal salvaje que está delante de mí en el zoológico”. Todo esto dura unos cinco minutos. “Le di la oportunidad de morderme”, dice Brody, tras romper el contacto visual con la ardilla. “No lo hizo”.

Adrien sigue arriesgándolo todo, todavía está dando a las ardillas del mundo la oportunidad de morderle, pero últimamente las cosas han estado saliendo como él quiere. Mantiene una feliz relación con la diseñadora de moda Georgina Chapman. (Debido a que Chapman estuvo casada anteriormente con Harvey Weinstein, Brody se ha convertido nuevamente en un foco de la prensa). “La vida funciona de maneras misteriosas, digámoslo de esa manera”, dice sobre la relación. Y luego, más tarde, sobre la extraña forma en que su relación se ha convertido en algo de interés para el público: “¿Qué podría decir respecto a eso que lo convierta en algo diferente de lo que es?”.

Encontró su camino de regreso a Hollywood, primero en pedacitos y luego todo a la vez. Pasó un tiempo escribiendo y luego haciendo Clean, una película sobre un trabajador de saneamiento de Nueva York con un pasado tortuoso, que se estrenará el próximo año. Ese proyecto le permitió explorar algunas ideas profundamente arraigadas sobre lo que hace que el drama sea convincente, en el cine y en la vida: “Todo tiene que ir en tu contra. Y luego, si lo logras, se convierte en algo heroico, y eso es la vida real, y eso es a lo que todos se enfrentan todos los días”. (También pudo disfrutar de una pasión que tiene desde hace mucho tiempo: su personaje conduce el Buick Grand National 1987 negro mate de su propiedad. “Es un coche hermoso”, dice. “Muy amenazante”).

Tras alejarse un tiempo y ganar una nueva perspectiva, descubrió que algunos “cineastas interesantes” le llegaban con cosas. Muchos de estos proyectos le han liberado de la responsabilidad de ser el protagonista obligado a sufrir para el disfrute del público. En cambio, hace un trabajo muy agudo con los personajes. Roba las escenas y clava las bromas.

En especial, le encantó interactuar con Brian Cox y Jeremy Strong en el rodaje de la tercera temporada de Succession. “Ahí estoy saltando con estos grandes tiburones en su elemento, en su océano”, dice Brody. “Y luego tengo que saltar y morderles de vuelta. Me gusta lo emocionante que es eso”. Conoce a un par de tipos como su personaje, dice, los famosos multimillonarios. Le pregunto si los ha llamado para preguntarles sobre los aspectos más importantes del estilo de vida de un ejecutivo. “No, no, ni siquiera necesito hacerlo”, dice sonriendo como si acabara de completar su formación como director de ventas. “¡Ya les he preguntado! ¡Ya lo sé todo!”. Brody dice que le ha gustado trabajar con el tono crudo y divertido del programa. “Tiendo a insistir en muchas de las cosas fuertes que veo en la vida”, dice. “Pero hay mucho humor incluso en las cualidades no tan agradables de la gente que conoces. Ciertas cosas que salen a relucir y piensas: ‘Eso ha sido extraño’ o ‘Eso ha sido un poco ofensivo”.

En otras ocasiones, se inclina hacia la comedia pura. En The French Dispatch interpreta a un hábil tratante de arte que reconoce, en un pintor encarcelado por asesinato, el futuro del arte contemporáneo –y, con alegría, se ríe–. Dirigida por Wes Anderson, es la última colaboración que le está ayudando a reescribir la trayectoria de su carrera. “Wes me ha permitido divertirme”, dice. Más que eso, parece que Anderson le ha mostrado al resto de Hollywood que Brody también puede divertirse. “No es algo que [Wes] haya tenido que sacarse de un sombrero”, dice Brody, con una encantadora insistencia en que ha aprendido a relajarse y divertirse un poco.

Por supuesto, Brody todavía disfruta del trabajo duro. Andrew Dominik, director de la película biográfica de Marilyn Monroe Blonde, elogió la actitud de Brody a la hora de no pulir su retrato de Arthur Miller. “Está interpretando a un personaje al que no se le ve con simpatía”, me dice Dominik. “Y a menudo, cuando un actor está interpretando un papel poco halagador, lo hace actuando como un idiota. Es una forma de decir: ‘Estoy jugando a ser un idiota, pero no soy yo’. Y el instinto de Adrien fue todo lo contrario “. Mientras tanto, Chapelwaite, estrenada este año, fue la típica actuación sufrida de Brody. La serie de Epix, adaptada del cuento de Stephen King Jerusalem’s Lot, era puro horror gótico, pero Brody, no obstante, fue capaz de extraer algo de su experiencia: interpretó a un hombre conducido a la locura después de tomar posesión de una casa embrujada.

Con el tiempo, Brody se ha vuelto un poco más sabio sobre aquello por lo que vale la pena sufrir. Para explicar este cambio, me cuenta una historia sobre una película que hizo hace más de una década. Wrecked era un incómodo thriller cuya acción comenzaba momentos después de que el personaje de Adrien estrellara su coche en un barranco y sufriera un ataque de amnesia (y algo peor). Brody aparece en casi todas las tomas con diversos grados de agonía. “Sólo se me ve gritar y golpearme durante un par de horas”, así lo describe. El rodaje fue brutal: el personaje tiene una pierna rota en la película, lo que significa que Brody se pasó la mayor parte de la producción arrastrándose boca abajo por el bosque. Después de un tiempo, comenzó a usar el dorso de las manos para gatear, ya que sus palmas estaban llenas de espinas.

Un día estaban filmando al lado de un río, y Brody notó que el agua que corría había tallado un pequeño estanque ovalado perfecto en el centro de una roca. En este estanque, Brody vio “un gusano que se ahogaba, ondulando en el fondo de la piedra”. Parecía una de las fotografías de su madre. Este pequeño gusano, ahogándose pero todavía retorciéndose hacia la superficie, peleando una batalla que Brody podía ver que estaba condenado a perder, lo llenó de emoción. Sabía que ésa era la razón por la que estaba sufriendo durante el rodaje: éste era su personaje en una sola toma. “Ese tipo no lo logrará, y es tan hermoso”, dice. “Es tan pintoresco y trágico, y abarca todo lo que estamos diciendo”. Le pidió al director que lo filmara.

Pero Wrecked era una película independiente, con poco dinero y poco tiempo. El director dijo que no. Brody preguntó de nuevo. El director volvió a decir que no. “Me lo comeré”, ofreció Brody. El director pidió su cámara. Brody se comió el gusano. “Fue repugnante”, me dice Brody. “Creo que me puse enfermo”. Hace una pausa. “Pero está en la película”.

Comparte esta historia conmigo en un sendero rocoso muy por encima de la soleada ciudad de Los Ángeles, el emocionante tercer acto de su carrera presentado como la autopista zumbando debajo de nosotros. Pensando en el gusano que se comió, Brody se pregunta ahora para qué sirvió realmente su sacrificio. “¿Qué gané con ello?”, pregunta. “¿Quién se dio cuenta?”. Wrecked fue una película indie con muy pocos espectadores, y hay que buscar la escena para verla. Sabe que no tenía por qué hacerlo. “Pero de alguna manera”, dice, “me sentí obligado a hacerlo”.

Creo que lo que ha aprendido es algo sobre sus propias expectativas. Algo liberador, quizás. No es necesario que crea que comerse un gusano convertirá una buena película en una excelente. O que arreglar las piedras subterráneas, las que nadie verá nunca, le dará sentido a una renovación de años. Hacer lo difícil no siempre es la respuesta. El sufrimiento no te convierte en un mejor artista, y definitivamente no te convierte en una persona más fácil de tratar. Pero no puedes aprender de qué estás hecho realmente sin tu parte justa de sufrimiento.

Unas horas antes, le había preguntado por qué se había aferrado a su castillo; si, una vez que la renovación comenzó a prolongarse, había pensado en deshacerse de lo que se había convertido, ineludiblemente, en un recordatorio muy costoso de una situación difícil. Consideró la idea. Por supuesto que sí, me dijo. ¿Cómo podría no haberlo pensado? “Podría haber vendido. Podría haberme salido de inmediato y haber dicho: Esto es demasiado”, me aseguró. Y luego, como si fuera la cosa más obvia del mundo, añadió: “Pero no puedo hacer eso”.

*Sam Schube es subdirector digital de GQ.

**Entrevista originalmente publicada en el número 279 de GQ.

Fotografía: Jason Nocito

Estilismo: Jon Tietz

Peluquería: Thom Priano para R+Co. Haircare

Maquillaje: Kumi Craig para The Wall Group

Tailoring: Ksenia Golub

Set design: Robert Sumrell para Walter Schupfer Management

Producción: Eric Jacobson de Hen’s Tooth Productions

[Photos & interview- GQ Magazine, 2021] Adrien Brody Finds His Chill.

October 14, 2021

Nearly 20 years after winning an Oscar and staking his claim as one of his generation’s most serious actors, Adrien Brody is finding a glorious new gear.

Adrien Brody comes bearing fruit. We meet in the parking lot at the base of a popular Los Angeles hiking trail, and he quickly hands over the bounty he’s prepared for us: a plastic container full of cherries and watermelon, along with a couple of bottles of water, some fresh-squeezed orange juice, and two pieces of buttered toast wrapped in a paper towel. He’s a charmer, no doubt—but also an actor who relishes doing the deep work of preparation, no matter the role. We eat sitting on the curb. It’s not quite nine in the morning. The cherries are terrific.

Brody is 48 now, and has been acting professionally for more than 30 years. In that time, he’s become known for the intensity of his commitment to the job: losing weight or gaining muscle or crawling across the forest floor for a part. “I would do whatever it takes for a role,” he says, “and everybody in my life understands that and respects that.” Like all actors, he’s had highs and lows, but maybe because of that intensity, Brody’s highs have felt higher—and his lows perhaps lower—than many of the actors we think of as his peers, and whom he calls his friends. He is still the youngest best actor winner in Academy Awards history. He also decided, not long ago, to spend a few years doing anything but acting.

This fall marks an unusually prosperous stretch for the actor. He’s in the third season of Succession, in which he’ll play an activist investor butting heads with the Roy family. After that comes The French Dispatch, his fourth film with director Wes Anderson. (Their fifth is already under way.) And sometime next year, he’ll appear as two legendary figures: the playwright Arthur Miller, in Blonde, the Netflix film about Miller’s wife Marilyn Monroe, and the basketball coach Pat Riley, in Adam McKay’s HBO series about the 1980s “Showtime” Los Angeles Lakers. Keenly aware of how often these things are left to chance, he’s excited that so much is happening at once. “I did a lot of fun stuff, but now we’re catching it at a good moment,” he says. Brody has always applied his maximum-effort Method approach, no matter the quality of the material. And oftentimes, his work was the best thing about the films in which he appeared. Now, though, he’s got a run of parts in projects with auteur-level creators that finally seems properly calibrated to his abilities—and that seems likely to show audiences a different kind of Adrien Brody.

When we meet, the Lakers series is still in production, and as we set off on our walk, Brody—in hiking boots, a Yankees cap, and aviators—explains that something a little strange is happening with the Riley role. Brody didn’t know much about the coach prior to preparing for the part, but he quickly learned that Riley’s story was more complex than he realized. Before Riley became a Hall of Fame coach, he had been a college hoops star, Brody learned, and then a reserve on a title-winning Lakers squad. After a nine-year pro career, Riley hung it up at 30 and, as Brody says, “found himself out in L.A. trying to figure out what his place was within the sport, and not really being able to accept early retirement.” After the Lakers’ then head coach suffered a horrific cycling accident, and the assistant coach who replaced him was subsequently fired, Riley wound up in charge of what would become the signature team of the 1980s. “One man’s misfortune, essentially, created an opportunity,” Brody explains. When McKay was casting the show, he and Max Borenstein, the series writer, needed an actor who could reflect the coach’s duality of spirit. Brody seemed perfect, “because he is a unique mixture of stylish confidence and vulnerability,” McKay tells me in an email. “And that’s a perfect description of Riley. Although Riley obviously doesn’t advertise or isn’t quite as comfortable with the vulnerability as much as Adrien is. But it’s clearly there.”

That’s the Riley he’s been thinking about: not the swaggering, Armani-suited icon but a young man worried that his best years are behind him, baffled by the circumstances that have landed him in what should be an ideal position.

It’s funny, Brody says, just how much Riley’s story seems to echo his own. Living with the comparison these last few months has given him ample reason to think back on the strange storm that seemed to settle over his life and career after he won his Oscar, in 2003, for his work in The Pianist. Back then, Brody struggled with the same sort of contradiction Riley faced when he was handed the reins of the Lakers: He was ostensibly on top of the world and yet felt unable to control the trajectory of a career that might have peaked terrifyingly early. In Brody’s case, the rush of fame and work that followed the film provided a measure of security, but the experience also left him depressed and with an eating disorder, and it permanently reordered the expectations—his own and the industry’s—about how his career should go, about what success might look like.

As he’s explaining all this, pausing for winding digressions about the nature of luck and the vagaries of independent film production, we’re stopped in the middle of the trail by a leather-skinned hiker with a thick New York accent. He recognizes the famous actor and introduces himself as Jack. He tells us that he used to know Gerald Gordon, an acting teacher with whom Brody took some classes when he first moved to Los Angeles. Jack explains that Gordon once prepared him for just this moment, having instructed him to send along Gordon’s best wishes should Jack ever happen to run into Adrien Brody. Which sounds improbable, only it’s exactly what has just happened. Jack seems as confused as we are. Brody offers his appreciation and elegantly ends the conversation.

Perhaps thanks to Brody’s open-to-the-moment training as an actor, or maybe just his congenital sensitivity, humdrum events like these—a hike, a chat with a friend of an old teacher, a discussion about what he’s working on these days—have a way, in his life, of feeling freighted with a special charge. Metaphors, I learn over the course of our time together, tend to follow him around—some days like a litter of puppies, others like a colony of angry wasps.

He’s spent his career pouring every ounce of himself into his roles. But right now, with the Riley job and everything else around it, he seems ready to learn from the work. Helpful lessons abound, if we’re ready for them. “I’m just trying to live openly and fearlessly,” he’ll tell me later.

As we make our way up the hill, Brody pushes the pace. He turns back to me. We’ve been hiking for maybe 15 minutes. “So, anyhow,” he says, “that’s how, if you’re lucky enough, you can find new chapters opening up for you.”

Brody spent the summer shooting the Lakers show in various locations across Los Angeles. Every morning, he’d fold his lanky frame down into his blacked-out, souped-up, stick shift Fiat, and pilot it from his home in the Hills to wherever the production was based that day. He quickly came to love his commute—or maybe less the specific commute than the small joy of finally getting to have one. Much of his work as an actor has taken place in less comfortable climes. He long ago noticed that his friend Owen Wilson somehow managed to always wind up acting in movies that shot in town. Brody wasn’t so lucky. “Owen would live in Santa Monica and have a movie in Santa Monica,” he says. “I’d be in Bulgaria in wintertime, and Owen would go down to Santa Monica, like five blocks, and probably be allowed to go home for lunch. It’s an amazing thing,” he says, having a job he can drive to.

It is true that if you were making a movie set in Santa Monica, you might not cast Adrien Brody. If, however, you were making a film that needed a face easily contorted into Eastern European-inflected despair, or that required the sort of actor who might regard a low-budget indie production in the Balkans as a kind of glorious adventure, Brody would be your guy.

Some of this is plain anatomy. He’s got the ski-slope nose, and the wide, deep-set green eyes, and a pair of eyebrows tilted up in permanent expectation. He looks wry but also a little sad. His voice—raspy, nasal, flecked with wiseguy—feels out of time. Wes Anderson appreciates this quality. “A rare thing with Adrien is that, if it became necessary for him to suddenly have to work in about 1935, rather than 2021, he could do it,” he tells me in a drolly narrated voice memo composed in response to my questions.

Brody comes by it all honestly. His mother, the photographer Sylvia Plachy, left Budapest for Vienna as a teenager, around the time of the Hungarian Revolution, and eventually arrived with her family in New York, where she would later begin shooting for the Village Voice. His mom’s life and work gave her an ability to “see the complexity that most people miss, everywhere around them, and catch it. And immortalize it. And through that lens, I’ve seen the world,” he says. He was a sensitive kid, upset about that quality in himself until he realized that it could be a gift too. Performing opened up a new way of relating with the world, he says: “Fortunately, there were these outlets: There were wonderfully complex human beings to step into, that I could relate to in one way or another. And purge, I guess, or, participate in another human being’s suffering, and not feel alone in my own. And then understand the universality of all of our suffering and joy, but embrace the moments of joy and honor the vast suffering that unfortunately is the pervasive underlayer.”

Mom came back from an assignment to shoot at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts with a feeling that her only child—a budding magician and a natural performer—might like to study acting formally. Before long, he was taking four acting classes a day at LaGuardia High School and eventually had booked a part with Francis Ford Coppola in New York Stories.

That one-day job provided lessons that endured: When the script called for a couple of girls to show a strong aversion to the awful cologne being worn by Brody’s character, the director doused the teenage Brody. “Coppola went full Method and poured a bottle of really shitty cologne all over me, so that the girls had something to react to,” Brody recalls.

When Brody was 19, Steven Soderbergh directed him in his Depression-era film King of the Hill. Anderson remembers seeing it with Owen Wilson and being captivated by Brody. “It was one of those entrances where you can just feel instantly, Oh, this is a movie star!” he says. “He sorta smiles his way through it a bit, and he seems so relaxed. And he just grabs you, instantly.”

For a while, stardom for Brody seemed just on the edge of the frame. He scored a big role in The Thin Red Line, only to learn that director Terrence Malick had mostly cut him out of the film, and stole scenes in Spike Lee’s Summer of Sam as a liberty-spiked New York punk. Brody kept plugging away.

As we talk, the trail ends and the two of us are deposited out of the canyon and onto a quiet street, a leafy cul-de-sac plump with large homes. Up ahead is the road that will lead us gently back down the hill, to the spot where we left our cars. Brody has a different idea. “I know another way out,” he says, appending a bit of a warning. “But it’s crazy.” Sure enough, he locates a new trail. It’s a narrow, steep single-track path that is presently baking in the midmorning heat. We take it.

It is Adrien Brody’s gift, but maybe more often his curse, that he lives for difficult roles. And not just the difficult ones—the ones that beat him up physically, that test his sanity. “I always go, ‘Why did I take this? Why do I want to do this?’ ” he says. “I’m very excited to do almost anything for a character. Like, I’ve eaten worms. I eat ants. I jumped out of helicopters. And then only afterwards you go, Wow, that was really dumb. Like, why did I do that?”

The answer is always the same: “Because you want to be fearless. It takes over any better sense of judgment that you should have, and you just go with it.”

He was 27 when Roman Polanski gave him the chance to put his thoughts about acting and suffering to the test. In The Pianist, a true story of endurance and devastation, he played the title character, Władysław Szpilman, a Jewish musician who survived the Nazi occupation of Warsaw. To prepare, Brody carved his life down to the bone. He sold his car and disconnected his phones. He gave up his apartment and put his things into storage. He spent his days alone in hotel rooms in Germany and Poland, practicing the piano.

“It was an enormous responsibility, and it changed me,” he says. Physically, the shoot was a nightmare. He was depressed for a year after production wrapped, and unhappy with a body ravaged by a crash diet that got him down to 130 pounds. The whole thing left him with a sadness that lingers still. “But I had no idea what was coming,” he says. “I had no idea.”

“I aspired for more, and it felt like my theory of contributing and pouring my blood, sweat, and tears into a project didn’t yield the results.”

Of course, The Pianist was rapturously received—most especially for Brody’s haunting performance. He was nominated for an Academy Award and was seemingly admitted to that rarefied realm reserved for our finest, most committed (and possibly most berserk) actors. He lodged in the public imagination as perhaps the next Robert De Niro or Daniel Day-Lewis—the off-kilter, not-traditionally-handsome-but-still-obviously-sexy leading man who will be every director’s first choice for every serious movie made for the rest of his life.

The week of the Oscars, Brody got a call from Jack Nicholson—they were both up for best actor, alongside Day-Lewis, Michael Caine, and Nicolas Cage. The United States had just sent troops to Iraq, and Jack called the nominees up to his house in the Hills to talk about how they should respond. It was a shock. The first time they’d met, Brody says, “He was calling me Brophy, and now Jack’s inviting me over to his house. I’m there with Michael Caine and I’m there with Nicolas Cage and they’re sipping scotch and they’re smoking cigars and we’re sitting around in a little circle.” All but Brody were previous Oscar winners. Nicholson suggested that they not attend the show, in protest of the war. Brody said, “Hey, I don’t know about you guys, but I’m going. But I agree with you: I think that whoever is called to the stage has some responsibility to acknowledge what’s going on.” He just didn’t think it would be him.

And then it was. Brody hadn’t expected to win—the morning of the show, he remembers sitting on the curb on Beverly Boulevard outside a diner in Hollywood, overwhelmed at the enormity of it all, while his visiting parents waited for him to collect himself. But the win wasn’t dumb luck, either. He had put everything he had into the role, and the experience seemed to solidify his conviction that, with enough effort, he could embody and portray the rawest extremes of human experience. It was insane to think he could come close to understanding the suffering of a Holocaust survivor like Szpilman, but there was a sort of euphoria in the effort of trying. “It was like the hardest thing I experienced on so many levels, and then anytime I started wallowing in my own minute suffering, I had this perspective,” he says. He learned a simple, indelible lesson: Making great art is painful. Which is why it’s also pretty much the only kind of art worth trying to make.

His secret, if you could call it that, was that he wasn’t always acting. “I’ve worked with actors who are brilliant and don’t look insincere, but can merely act. They can create,” he says. “It’s a wonderful magic trick. They can act like they love you, and they really don’t. And it takes work for me.” In one scene in The Pianist, he had to clamber over a wall, bust his ankle while landing on the other side, and stumble off, limping. So he stuffed a sharp rock into his shoe. It hurt to land on, and then to walk on, too. “Why have to think about acting a limp?” he asks now. “Just hurt for a minute. Just do it.”

Even now, working through a series of virile icons of American masculinity—Riley; what Brody calls his “shark” of a Succession character; Marilyn Monroe’s husband—this way of thinking comes in handy. “There’s no swagger without damage,” he says. “In fact, probably, most people swagger as a result of a lot of damage.” A swagger, he reasons, being itself a kind of limp.

The audience might only catch the smallest glimpses of this—the armature of pain Brody erects beneath each character’s surface. But he knows it’s there. “That’s essential, at least for my process,” he says. “I don’t always need a rock. But I do often have a rock.” An actual rock, he clarifies, can be useful to convey all manner of emotions, even if his character doesn’t have a foot problem.

“Now you’re learning all my secrets,” he says, laughing. “Fuck. Even when I’m not limping. That’s why I look so melancholy. I have a fucking rock under my foot.”

One thing Brody stresses as we walk is how unlikely this all was—how many tiny impossible things have to go right to make any movie, let alone one that sends its actor through the gauntlet of awards season and out the other side with a business card that reads Hollywood Darling. “You know, those things don’t necessarily happen, ever,” he says. “But the expectation can be that they should happen regularly.”

It took him a while to outgrow that expectation, and so the years that followed his Oscar win were disorienting. “I had been acting for 17 years, and people would recognize me, and it was normal,” he says. “Paparazzi, they couldn’t care less. No one followed me. No one started behaving strangely. No one did odd things. And then a lot of oddness happened.” After the Oscar, every interaction with other people was somehow different. “It was as if a storm rolled in,” he says. “Everything started blowing away—the life I knew.”

Don’t change, people kept telling him. Don’t change. So he didn’t. But then they went off and changed. They talked to him differently. Friends wanted to go into business with him. Photographers wanted to take his picture. Directors wanted him for their movies. None of it quite felt right. “It feels like it was a decade of finding out who and where I was. A lot of living and losing and winning and losing,” he says.

For a while, he had the uniquely bad luck of appearing in a number of panned projects by particularly well-liked filmmakers. He did The Village, M. Night Shyamalan’s first big wobble. Peter Jackson’s big-budget remake of King Kong. Wes Anderson’s dreary The Darjeeling Limited. Rian Johnson’s The Brothers Bloom. All logical choices, on their merits; all performances characterized by Brody’s uniquely intense brand of pathos; all unlucky outcomes, by harsh Hollywood accounting.

He dreamed of getting away—of finding a place somewhere in upstate New York, the kind of house his dad would point out in the real estate listings when he was a kid. His friends Mark Ruffalo and Vera Farmiga had places away from the city, proving that escape wasn’t incompatible with a Hollywood career. He was dating the actress Elsa Pataky at the time, and he thought they could do the same thing. “I had way too much attention for my liking, and I thought I could retreat, come in, do my work and have this honest… I don’t know why, but I imagined it would be simple.”

Brody being Brody, it was not simple. He was working on a movie in Serbia and poking around at real estate listings online when he found the Stone Barn Castle. The enormous cobblestone-and-cement home, some four hours outside New York City, featured stables for horses and even an apple orchard. Brody was smitten. “I’d been dreaming of something dramatic,” he says. He bought it, and surprised Pataky with the purchase.

They set about on a massive renovation. But the relationship ended before they could move from the guest house to the main building.

It would be three or four years before Brody could move into the main house himself, so intensive was the construction. What began as an escape became an all-consuming project, equal parts distraction and balm. He traveled to India and China to find the right materials. He bought church windows and hand-hewn beams from farms in New York and Pennsylvania and Canada. He had a team re-pointing stones for four years. Free home makeover advice from Adrien Brody: Don’t worry about re-pointing stones. “I employed a group of men to come and chisel away every stone, underground and up above. And then when it’s all done, it looks the same. It is a little bit neater.” That feeling suffused the whole project: “I don’t know what the purpose of it really is yet,” he says. “But it is an achievement.”

And then, five or six, or maybe eight, years ago, he looked up and realized that his day job wasn’t getting any easier. He was still applying the maniacal effort that shot him to fame, but the work no longer seemed to repay his exertion. “There was this protracted period where I realized that that path wasn’t working, for whatever reason,” he says. “I aspired for more, and it felt like my theory of contributing and pouring my blood, sweat, and tears into a project didn’t yield the results. There was a disconnect somehow to what I had done for so long, and it just wasn’t working.” So he stepped back. He finished off the projects he was working on, and said no to the ones that came in. He grew his hair long, and started wearing a beard. He hung out with artists and started painting. He made music. He traveled the world.

Eventually, he came to understand the hobbies he’d thrown himself into less as attempted diversions from acting and more as ways of buttressing his belief in his own creativity—different, and often less painful, ways to channel his energy. “That’s living, that’s not running away,” he says. “It’s being present with something, and trying to create something that endures.”

Initially, our plan is to meet again the next day to talk over lunch. But as we nosh in the parking lot after our hike, we figure: Why not do this again tomorrow? We’ll have to get up a bit earlier, to account for the heat, but Brody is game and so am I. Later that night, he sends along coordinates that I follow, at 7:30 the next morning, to a trailhead near an eerie old abandoned zoo complex. This time, Brody has packed a container of sliced peaches and blood orange, and brought along little oyster forks we use to spear the fruit.

Almost immediately, Brody’s attention is captured by a squirrel hiding in a nearby rock. He crouches, willing the creature over, and apologizes to the squirrel for not having brought food. “I’m sorry,” he says. “I’m not prepared because I didn’t know I would meet such a cute little dude.” Brody is patient and still, and it’s working—the squirrel comes within a few inches, then retreats, then comes closer again. They repeat the dance until the animal is a whisker away from Brody’s hand. “Adrien Brody makes very authentic squirrel noises,” he says, anticipating how the interaction will appear in this story, “then communes with the wild animal right before me in the zoo.” This lasts about five minutes. “I gave him his chance to bite me,” Brody says, after he’s broken eye contact with the squirrel. “He didn’t do it.”

Brody is still putting it all out there—still giving the squirrels of the world plenty of chances to bite him—but lately things have been breaking his way. He’s in a happy relationship with the fashion designer Georgina Chapman. (Because Chapman was previously married to Harvey Weinstein, Brody has again become something of a tabloid fixture. “Life works in mysterious ways—put it to you that way,” he says of the relationship. And then, later, about the strange way his relationship has come to be something in which the public feels invested: “What could I say about that that would make it anything other than what it is?”)

He found his way back to Hollywood, first in bits and then all at once. He spent a while writing and then making Clean, a movie about a New York sanitation worker with a tortured past, which will be released next year. That project let him explore some deeply held ideas about what makes for compelling drama, in filmmaking and in life: “Everything has got to work against you. And then if you make it through, that’s somewhat heroic, and that’s real life, and that’s what everybody faces every day.” (He also got to indulge a longtime passion: His character drives Brody’s personal matte-black 1987 Buick Grand National. “It’s a beautiful car,” he says. “Very menacing.”)

After sitting things out for a little while and gaining some new perspective, he found that “interesting filmmakers were coming to me with things.” Many of these projects have freed him from the responsibility of being the leading man forced to suffer for the audience’s enjoyment. Instead, he gets to do sharply observed character work. He steals scenes, and cracks jokes.

He especially loved tangling with Brian Cox and Jeremy Strong while making Succession‘s third season. “Here I am jumping in with these big sharks really in their element, their ocean,” Brody says. “And then I have to jump in and bite back. I like the thrill of that.” He knows a couple of guys like his character, he says, billionaire hotshots. I ask if he’s hit them up to pick their brains on the finer points of the executive lifestyle. “No, no, I don’t even need to,” he says, smiling like he’s just completed his own piece of corporate dealsmanship. “I’ve already picked it! I already own it!” Brody says he’s enjoyed operating in the show’s raw, funny register. “I tend to harp on a lot of the heavy things that I see in life,” he says. “But there’s a lot of humor in even the not-so-nice qualities of people that you know. Certain things that come out and you go, ‘That was odd,’ or ‘That was a little offensive.’ ”

Elsewhere, he’s tipping into pure comedy. In The French Dispatch, he plays a slick art dealer who recognizes, in a painter imprisoned for murder, the future of contemporary art—and, joyfully, he gets laughs. Directed by Wes Anderson, it’s the latest in a collaboration that is helping him rewrite the trajectory of his career. “Wes allowed me to have fun,” he says. More than that, it seems that Anderson showed the rest of Hollywood that Brody could have fun, too. “It isn’t something he had to pull out of a hat,” Brody says of Anderson, charmingly insistent that he has learned to loosen up and have a little fun.